Living in unprecedented times has become the norm since early 2020, and just when a light at the end of the tunnel begins to shine through, a new set of challenges always seems to materialize.

We are familiar with the current challenges – inflation running at four-decade highs, escalating geopolitical risks, and a monetary policy regime purposely restricting economic growth. Altogether, we believe this may be a recipe for a recession – but what kind of recession and how severe it could be are critically important when implementing a fixed income strategy.

What Really is a Recession?

Technically, the bookends of a U.S. recession are determined by a committee of economists at the National Bureau of Economic Research, or the NBER for short, who judge the state of the economy with an almost subjective set of guidelines.1

However, what truly matters is when market participants believe we are in recession. The rule of thumb for defining a recession is any period that experiences two consecutive quarters of negative growth, as measured by real gross domestic product (GDP). For context, this rule has been breached seven times in the U.S. since 1960; each also deemed a recession by the NBER.2

Using the rule of thumb, we may already be in the midst of a recession considering U.S. real GDP contracted by -1.6% during the first quarter and some observers believe it will contract by another -1.2% in the second quarter of 2022.3

While defining and labelling a recession is helpful, we must recognize that each recession is unique in terms of causation and repercussion. Trying to ascertain the potential length and ramifications for individuals and investors is a far more important and difficult task.

A Recession Driven By Inflation Fears Transforming Into Growth Fears

The pandemic-induced collapse was the shortest recession ever recorded, lasting only two months from peak-to-trough due to extraordinary fiscal and monetary intervention, which quickly restored confidence. Unfortunately, the unprecedented government spending and rapid growth in the money supply may also have contributed to the rise in inflation which began in mid-2021 as easing lockdowns and cash-flushed consumers severely pressured unprepared supply chains with demand for goods and services.

Once thought to be transitory, elevated inflation measures have extended far longer than most expected and in greater severity as the escalating Russia-Ukrainian War and prolonged lockdowns in China added significant fuel to the fire. In response, global monetary entities have been forcefully shifting their regimes from a historically accommodative policy to more restrictive stances, including aggressive rate hikes, slowing or reducing the pace of Quantitative easing measures, and unwaveringly hawkish forward guidance to combat rising prices.

The byproduct of this shift in policy has been an unparalleled rise in risk-free rates and a sharp repricing of assets, the result of which has been to aggressively tighten financial conditions .4 Moreover, central bank chiefs have been explicit about their commitment to reining in prices and not letting inflation expectations become unanchored, even at the expense of employment and growth.

As a result, the market has begun to add the possibility of a hard landing – or even a recession – to its long list of worries. Markets have rapidly begun to price in a rising probability of a downturn in growth. For instance, commodity prices have sharply retreated from local highs, inflation expectations somewhat eased in early July, and corporate credit spreads markedly widened.

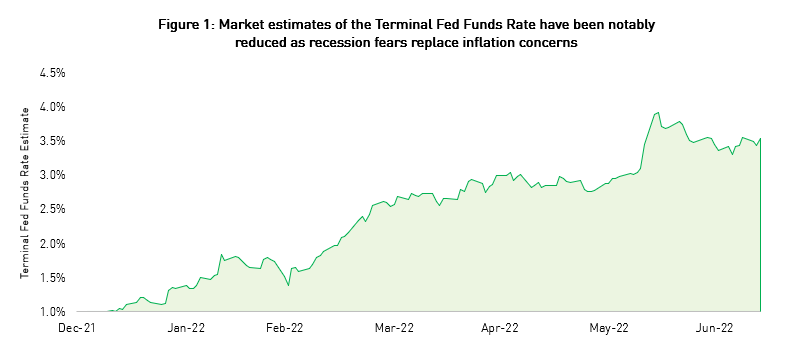

Moreover, market estimates of the Federal Reserve’s terminal Fed Funds Rate (the rate expected to be reached at the end of this hiking cycle) have been reduced by ~38bps, from a high of ~3.93% in mid-June to just ~3.55% today.5

Also, it is important to note that markets are now anticipating the Fed will have to cut rates by as much as ~50bps in the latter half of 2023 to counteract recessionary pressures!

Source: Bloomberg. Data as of July 13th, 2022

Hard or Soft Landing

The Fed and many commentators still believe that a ‘soft landing’ – characterized by slower growth and lower inflation, but no recession and not a dramatic spike in unemployment – is the central case.6 We believe it will be quite challenging for monetary authorities to achieve such an outcome, and while we do not think a recession is inevitable, we do believe the risk of one is higher than the Fed and most market observers estimate.

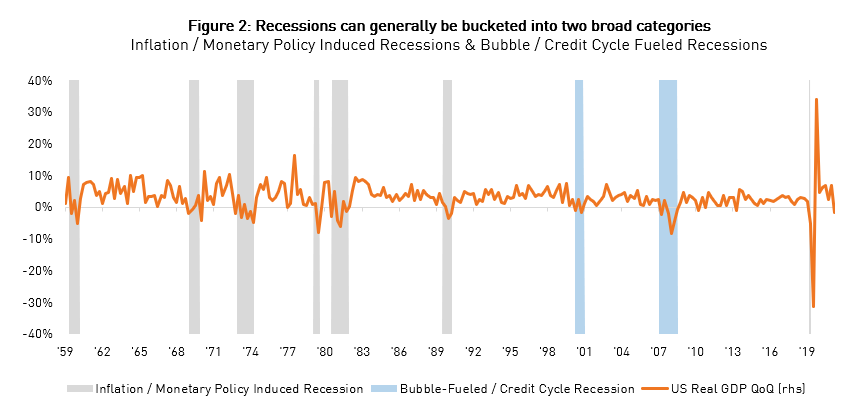

Estimating the potential depth of a slowdown or recession is a challenging task that requires current and historical context. The previous eight U.S. recessions (excluding the Covid-induced slowdown) have had an average contraction of ~11 months peak-to-trough, followed by an average expansion of ~5.4 years.7 Although plenty of dispersion can be found within these averages, the eight recessions in question can generally be bucketed into two broad categories: (1) inflation and monetary policy-induced recessions and (2) bubble-fueled credit cycle recessions.

The dot-com and housing bubbles of the early and mid-2000s can be categorized under the latter, while the others can be labelled as more traditional downturns. What makes the current situation challenging to decipher is the fact that it has the ingredients of both.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Bureau of Economic Research. Data as of March 31st, 2022

Classic recession kindling is well underway as central banks are forced to destroy demand as their only means of bringing elevated inflation down. Simultaneously, a higher cost of capital has put pressure on housing and some of the more speculative and levered asset classes, whose rise was fueled by a decade-plus of easy monetary policy, a deluge of expansionary fiscal support, and broad deflationary pressures post-Great Financial Crisis.

Making things even more complicated is the deviation between the healthy current state of the U.S. consumer versus consumer sentiment levels. For instance, the U.S. labour market is historically hot, with the unemployment rate sitting at only 3.6% and nearly 2x the number of job openings available per unemployed person.8 This buoyant employment situation, combined with the persistence of multi-decade high inflation statistics is giving policymakers, especially in the United States, cover to be aggressive even as the impact of tightening financial conditions on other sectors of the economy becomes evident.

Contrarily, a survey that measures consumer sentiment nosedived to its lowest levels ever in June, while a measure of consumer expectations also featured an increasingly pessimistic outlook.9 Similarly, corporate balance sheets have proven resilient thus far, with earnings and margins at or near all-time highs. Yet many market participants are concerned that a weakening consumer and rising capital costs will lead to negative corporate guidance revisions in the coming earnings season.

These coinciding elements have led to heightened uncertainty and a stark divergence in opinion regarding the potential magnitude of the ensuing recession. One camp suggests that we’re on pace for a hard landing characterized by prolonged negative growth and skyrocketing unemployment – while the other camp believes we’re due for a soft-ish landing characterized by a short-lived and subdued slowdown.

Our Views and the Impact on Strategy Positioning

While we remain data-dependent, our house view remains that growth will slow more than the market currently believes. Although we cannot predict whether or not a technical recession will occur, should one materialize, we agree that strong balance sheets and the hot employment market will combine to make it only a moderate one. With that said, we are slightly more concerned about the state of the Canadian economy, given its highly indebted consumer and greater reliance on a vulnerable housing sector, and the already aggressive actions by the Bank of Canada.

Consequently, we believe the Bank of Canada may end its hiking cycle sooner than the market currently expects. This is why we are currently more comfortable adding interest rate risk through shorter-term Canadian bonds that provide us with an adequate tradeoff between capturing higher yields and limiting drawdown risk due to rising rates (i.e., the chance of terminal rates being higher than current market expectations). In contrast, from a credit perspective, we have notably shifted out of Canadian exposure in favour of U.S. credits, particularly those we believe can be resilient and provide capital appreciation opportunities.

As a whole, current market dynamics still warrant a disciplined approach in terms of risk-taking. While we do not aim to time the bottom of the market, especially with a slowdown looming, we are cautiously upgrading our portfolios with quality credits at what we believe are attractive levels.

We believe taking advantage of these opportunities today can provide our investors with attractive risk-adjusted returns over the next several quarters.

1 According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, “A recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in production, employment, real income, and other indicators. A recession begins when the economy reaches a peak of activity and ends when the economy reaches its trough.”

2 Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Bureau of Economic Research.

3 According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow forecasting model as of July 8th, 2022: https://www.atlantafed.org/cqer/research/gdpnow.

4 Goldman Sachs Financial Conditions Index (FCI) is defined as a “weighted average of riskless interest rates, the exchange rate, equity valuations, and credit spreads, with weights that correspond to the direct impact of each variable on GDP.”

5 Source: Bloomberg WIRP U.S. Implied Overnight Rate. Data as of July 13th, 2022.

6 According to the Federal Open Market Committee’s mid-June Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), the Fed projects 2023 real GDP growth and unemployment rates to be 1.7% and 3.9%, respectively.

7 Source: National Bureau of Economic Research.

8 Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. Data as of June 30th, 2022.

9 Source: University of Michigan, The Conference Board. Data as of June 30th, 2022.

Important Information

The information herein is presented by RP Investment Advisors LP (“RPIA”) and is for informational purposes only. It does not provide financial, legal, accounting, tax, investment, or other advice and should

not be acted or relied upon in that regard without seeking the appropriate professional advice. The information is drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but the accuracy or completeness of the information is not guaranteed, nor in providing

it does RPIA assume any responsibility or liability whatsoever. The information provided may be subject to change and RPIA does not undertake any obligation to communicate revisions or updates to the information presented. Unless otherwise stated,

the source for all information is RPIA. The information presented does not form the basis of any offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of securities. Products and services of RPIA are only available in jurisdictions where they may be

lawfully offered and to investors who qualify under the applicable regulation. RPIA managed strategies and funds carry the risk of financial loss. Performance is not guaranteed and past performance may not be repeated. “Forward-Looking”

statements are based on assumptions made by RPIA regarding its opinion and investment strategies in certain market conditions and are subject to a number of mitigating factors. Economic and market conditions may change, which may materially impact

actual future events and as a result RPIA’s views, the success of RPIA’s intended strategies as well as its actual course of conduct.