Initially published in the Spring Edition of The Association of Canadian Pension Management's The Observer publication.

As we enter the second quarter of 2025, it seems that the uncertainty facing the market is only growing. Trade conflicts, war, political unpredictability, inflation fears, and stretched valuations present a combination of challenges that most market participants have not faced in their lifetimes. The recent sell-off in the equity markets is a reminder that financial markets often price extreme price moves as though they are highly unlikely to occur. In fact, despite recent widening, at the time of writing – the 7th of April – credit spreads, (the compensation investors demand for taking default risk) remain near multi-decade tights.

The paradox of market behavior is that we simultaneously tell ourselves that shocks are extremely rare, and that today’s problems are worse than yesterday’s. Neither story is true.

Myth 1: Crises are Rare

In contrast, most people’s mental models consign very large price movement to the realm of inconsequential probabilities. Most people remember the normal distribution from school, which unfortunately and inadvertently reinforces this bias. For example, the S&P 500 lost 12% in its worst day following the onset of COVID in 2020. That was roughly a 10 standard deviation event. Using the normal distribution, the odds of that occurring are one in 131 sextillion (131 x 1023). That means the normal distribution would predict that a day like that would happen less than once in 180 billion lifetimes of the universe. Yet it happened. As did the 1987 crash, the dotcom bust of 1999-2001 and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Each of these recent events caught the market by surprise even though we know that pandemics, financial euphoria and banking crises are regular features of the economy. This combination of recency bias and a neglect of base rates of probability leads people to ignore the tails of the distribution repeatedly, even though simple math cautions otherwise.

Myth 2: Today's Crises are Worse Than Yesterday's

On the other side of the equation, today’s troubles always seem more complex and less tractable than yesterday’s. That is for three reasons:

- Yesterday’s problems have been solved already, so we know how the story ends.

- Humans are prone to nostalgia and declinism (for evidence we need look no further than the appeal of the promise to “Make America Great Again” to millions of voters in the United States, twice).

Today’s world is uncertain, meaning that we cannot quantify the probability of any event or set of events occurring. History, by contrast, is known and therefore may be described as risky. For example, we know exactly how many times since 1927 the S&P 500 has sold off 20% or more but we cannot accurately estimate the probability that it will do so again this year.

When combined, the dueling narratives of (1) the extreme being less likely than experience has demonstrated and (2) today’s world being uniquely complex, is toxic to investors. It leads to confusion at best and paralysis at worst. So how to combat them?

The Art and Science of Risk Management

The power of storytelling

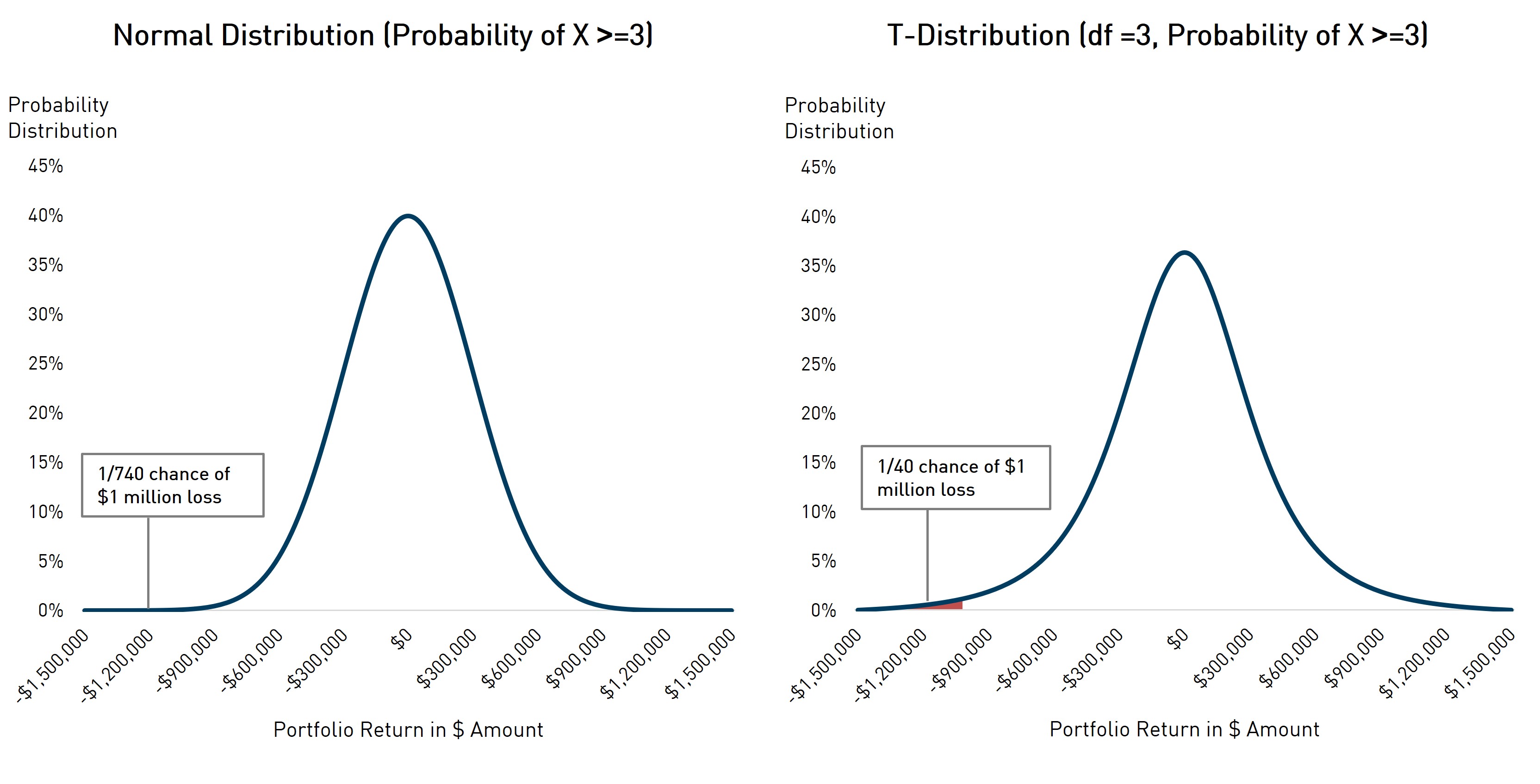

To make the example vivid, imagine a risk manager approaching a portfolio manager carrying two charts, one with the normal distribution and the other with a fancier, more appropriate distribution (one that has fatter tails). She says to the PM, “While you may think the probability of losing a million dollars in a 3-standard deviation event is one-in-740, as the normal distribution implies, it is not. Rather, it is one-in-40 as my distribution chart clearly demonstrates.”

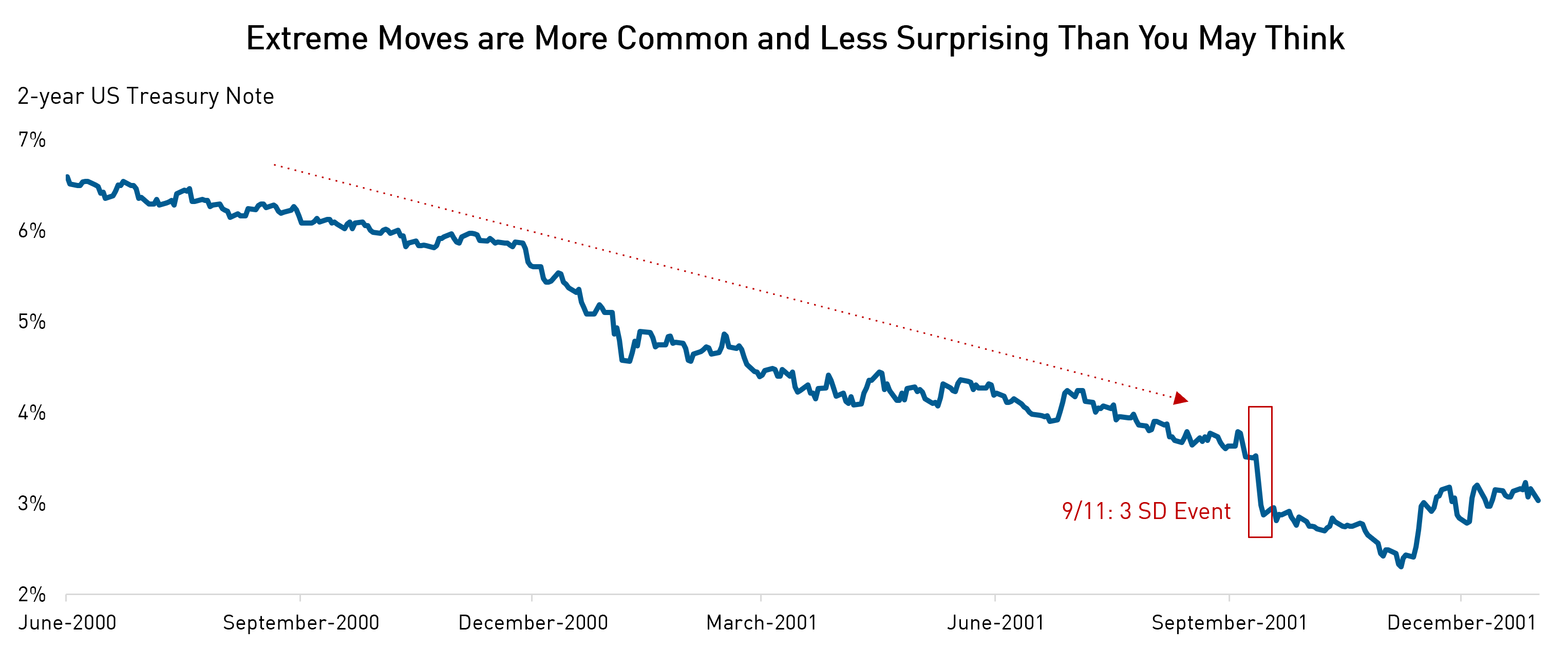

Now imagine she approaches with a different tactic. She pulls up her chair and tells the PM what she was doing on September 11, 2001. She describes what occurred and that it happened after the S&P had mired itself in a 25% bear market, the US Treasury two-year note had rallied over 300 basis points, and the Loonie had traded from $0.70 to $0.63. Then she shows him how his portfolio would have responded. He would not have lost a million dollars that day. He would have lost three million dollars. Nobody saw it coming, and that was after the huge moves that had preceded it.

Source: Bloomberg.

There are, of course, limits to scenario analysis like this. Since no two crises are the same, it is obviously not a prediction of future results – you don’t want to fight the last war. Uncertainty seems worse than risk, which puts the risk manager and the PM in danger of overcorrecting. The PM may be too young to relate at all (in that case the risk manager should have chosen a better example). Nonetheless, she got his attention. Only once that has occurred can they address the details of today’s situation and forge their path accordingly.

Putting the story into today’s context

The object is to bring experience to assessing the likelihood of a set of shocks that, while perhaps absent from history or not contemplated by off-the-shelf models, could portend unacceptable losses in the portfolios in question. By asking herself what may cause a given correlation to break down, a specific hedge to move in unexpected ways, or a counterparty to become adversarial, the risk manager is ensuring that the mental models and heuristics of the portfolio management staff have fat tails of their own.

Preparing for the Crises of Tomorrow

Today’s challenges are likely neither uniquely severe nor uniquely benign. They are part of the ongoing cycle of market evolution, where new risks emerge, and new solutions follow. Investors who acknowledge uncertainty while preparing for a range of outcomes – both extreme and ordinary – will be best positioned to navigate the markets. The greatest risk is not uncertainty itself, but the failure to account for its full range of possibilities.

Important Information

The information herein is presented by RP Investment Advisors LP (“RPIA”) and is for informational purposes only. It does not provide financial, legal, accounting, tax, investment, or other advice and should not be acted or relied upon in that regard without seeking the appropriate professional advice. The information is drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but the accuracy or completeness of the information is not guaranteed, nor in providing it does RPIA assume any responsibility or liability whatsoever. The information provided may be subject to change and RPIA does not undertake any obligation to communicate revisions or updates to the information presented. Unless otherwise stated, the source for all information is RPIA. The information presented does not form the basis of any offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of securities. Products and services of RPIA are only available in jurisdictions where they may be lawfully offered and to investors who qualify under applicable regulation. The RPIA managed investment strategies discussed herein may be available to qualified Canadian investors through private and/or publicly offered investment funds. Eligibility and suitability of investing in these funds must be determined by registered dealing representatives of RPIA or third-party dealers.

The use of hypothetical performance data is solely for illustrative purposes. Hypothetical performance is constructed based on the assumptions described within and with the benefit of hindsight. It must not be viewed as actual performance and in no way implies future performance. RPIA does not in any way assure any of the hypothetical performance outcomes described in this material. “Forward-Looking” statements are based on assumptions made by RPIA regarding its opinion and investment strategies in certain market conditions and are subject to a number of mitigating factors. Economic and market conditions may change, which may materially impact actual future events and as a result RPIA’s views, the success of RPIA’s intended strategies as well as its actual course of conduct.