What is a debt-for-nature swap?

Debt-for-nature (“D4N”) swaps have been around for decades. They were first proposed in 1987 by the World Wildlife Fund's Thomas Lovejoy, who saw them as an opportunity to deal with the problems of developing nations' debt. In the wake of the 1984 Latin American debt crisis, the environmental conservation efforts of highly indebted nations plummeted. Lovejoy proposed that restructuring debt and promoting conservation could be done simultaneously.

D4N swaps allow a developing country to dissolve a portion of its foreign debt in exchange for local investments in environmental conservation measures. This instrument enables countries to take action to protect their natural environment, while still being able to focus on other development priorities without triggering a fiscal crisis. Once established, the national government of the indebted country agrees to a payment schedule on the amount of the debt forgiven, usually paid through the nation's central bank.

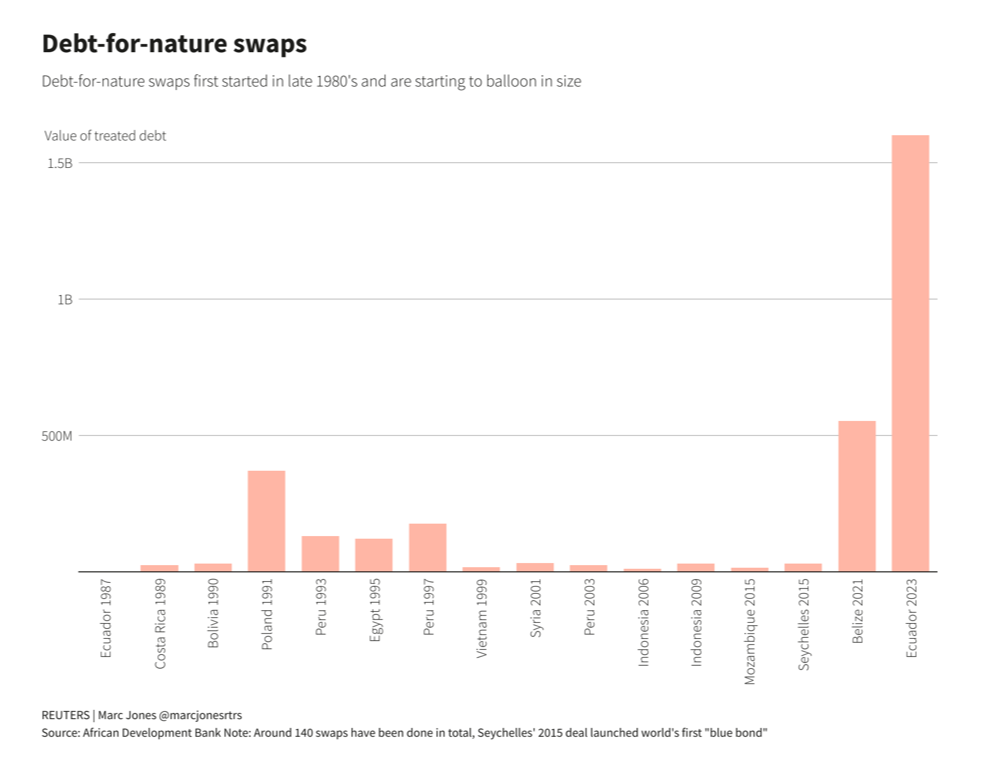

Conservation International (a US-based environmental non-profit) and Bolivia signed the first debt-for-nature agreement in 1987. Since then, D4N swaps have been used for conservation efforts in developing countries through more than 140 deals, including the first ever “blue bond” in 2015 with Seychelles. Typically, the countries that engage in the swaps have several threatened or endangered species, are experiencing rapid deforestation, and have relatively stable, often democratic, political systems.

The resurgence of debt-for-nature swaps today

Until last year, only one major bank was arranging D4N swaps, connecting countries with private investors to structure refinancing with conservation commitments. Credit Suisse (now UBS) established itself as a pioneer for this debt instrument, securing the world’s biggest D4N swap to date with the Ecuadorian government, buying back about $1.6 billion for $644 million. A $656 million “Galapagos Bond” maturing in 2041 will replace the old debt, accompanied by the country’s commitment to spend $18 million annually for 20 years to protect a marine reserve, which is used as a migratory corridor by sharks, whales, sea turtles, and manta rays.

In 2023, Bank of America Corp. became the second major bank to join this market in a deal with Gabon. With the ESG debt market estimated to grow to about $800 billion, according to Barclays Plc, nine global banks are now intending to explore similar transactions to capture a share of this market, focusing particularly on African and Latin American sovereign debts. For these banks, including the likes of Goldman Sachs, HSBC, Citigroup, and Barclays, D4N swaps allow them to reduce their exposure to political risk and default risk from governments with fiscal insecurity.

In December 2024, Bank of America Corp became a repeat dealmaker, helping Ecuador complete its second swap. This time, they unlocked $460 million to protect and manage the Amazon rainforest and wetlands through the Amazon Biocorridor Program. Following suit, a unit of CIBC arranged a sustainability-linked loan (backed by $300 million in guarantees from the European Investment Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank) with Barbados, that will generate $125 million in savings. This will allow Barbados to turn an existing sewage treatment plant into a modern water-reclamation facility that will support agriculture irrigation and improving the island’s sewage system.

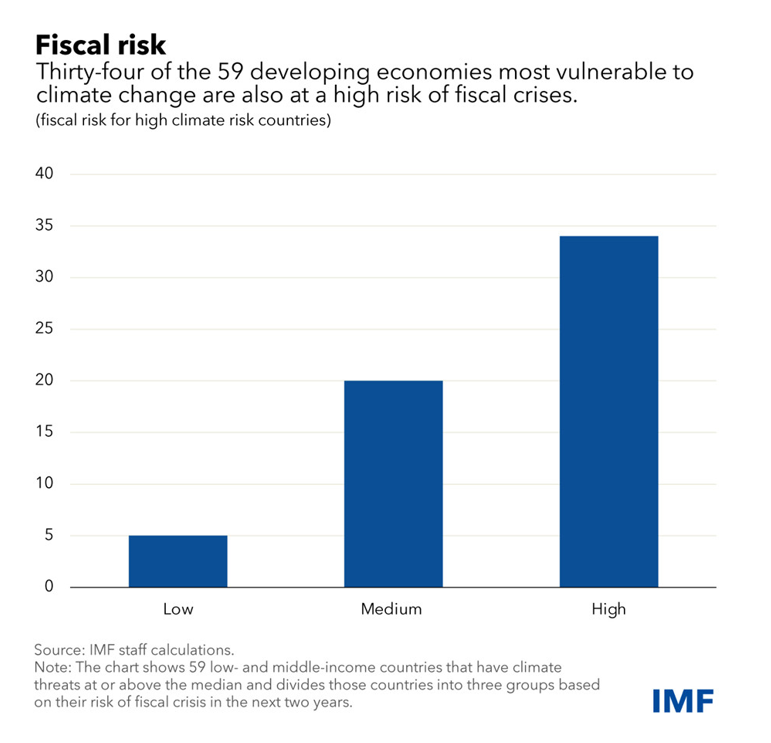

Today, countries with pressing fiscal problems exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador, face a biodiversity threat from expanding the agriculture and extractive industries they rely on for export revenues. D4N swaps seek to free up fiscal resources so governments can improve resilience without triggering a fiscal crisis or sacrificing spending on other development priorities. In fact, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that almost 60% of the developing economies that are most vulnerable climate-related risks, are also at high risk of triggering a fiscal crisis. However, according to the IMF, for D4Ns to have a meaningful impact, the number and size of the transactions must be scaled up significantly.

Far from the perfect solution

A D4N swap can only restore solvency for countries with unsustainable debt if it involves a sufficiently large share of their debt and substantial relief. To date, no swap has come close to achieving this goal, making it challenging for the public to view swaps as practical alternatives to debt restructuring. Additionally, grants and concessional loans from donors and development banks are scarce relative to the immense need for climate and nature financing, particularly for middle-income countries that do not typically qualify for grants. Moreover, restructuring is often only available to countries once their debts become unsustainable, and they lose market access.

Despite the general view that D4N swaps are mechanisms that can achieve positive environmental policy outcomes, they have yet to gain widespread approval. International organizations have raised concerns over the perceived inefficiency and risks of swaps compared to other financial instruments. D4N swaps can also take years to negotiate, making them expensive, especially considering some negotiations never come to a satisfying conclusion. Some swaps are also attracting criticism from non-profits, citing lack of transparency and consultation with local communities. In response, some banks are committing to consult with communities before completing any deals.

Additionally, although there is growing demand and interest for such an instrument, many investors still struggle to allocate D4N swaps as they combine emerging market debt with Treasury-market yields. As D4N swaps are illiquid, mostly smaller in size, and lack high yielding structures, many major investors are hesitant to jump in.

What's next for debt-for-nature swaps?

If these instruments seem familiar, it's likely because they resemble sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs). Since emerging in 2019, SLBs have been used by both private and public sectors to improve climate and environmental outcomes and are linked to the company’s achievement of climate or broader UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The coupon rate of SLBs is tied to a company's progress— or lack thereof— toward these goals, with the rate increasing or decreasing based on performance. However, in 2024, the SLB market began to experience a significant decline, with issuance dropping by 46%. The product has faced challenges in the US, driven by an ESG backlash and the continued influence of Donald Trump’s anti-climate agenda, which is expected to further hinder fundraising efforts. Additionally, concerns about greenwashing and growing regulatory scrutiny are proving to be a deterrent for investors in both SLBs and D4Ns. As a result, the D4N market remains relatively underdeveloped. Due to the high risk of default, investors have historically only bought the issued bonds after government agencies agree to insure them. From a structuring and allocation perspective, greater standardization and a more sophisticated understanding of the product is essential for this instrument to achieve its impact potential.

In October 2024, six nonprofits, including the Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, and the World Wildlife Fund, agreed to construct a shared pipeline of deals that will be subject to common standards. The group is excited about the instrument’s growth potential as a financial structure and believe D4N swaps may unlock as much as $100 billion of nature and climate finance. This year, Ramzi Issa, known for pioneering D4N swaps during his tenure as the former head of global structured credit and sustainable credit products at UBS Group, launched his own credit fund, Enosis Capital. Enosis will primarily focus on debt conversions, while also exploring opportunities to structure and advise on a diverse range of impact-driven transactions globally.

Like most forms of conservation finance, swaps can play a significant role in some circumstances. Although they can be riskier and time consuming, the recent Ecuador example proves that they are growing and could become increasingly beneficial to more countries. Swaps could create additional revenue for countries with valuable biodiversity by allowing them to charge others for protecting it. However helpful, they are unlikely to provide a universal solution for countries struggling with debt or confronting climate change, and they should not come at the expense of traditional debt relief efforts. In the future, we hope to see these swaps scaled up to complement existing instruments and strengthen resilience in countries on the front line of climate change and loss of natural biodiversity.

Sources

- World Economic Forum. (2023, June). Climate finance: Debt-for-nature swap. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/06/climate-finance-debt-nature-swap/

- Diálogo Chino. (n.d.). Explainer: What is a debt-for-nature swap? Retrieved from https://dialogochino.net/en/trade-investment/47862-explainer-what-is-debt-for-nature-swap/

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2022, December 14). Swapping debt for climate or nature pledges can help fund resilience. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/12/14/swapping-debt-for-climate-or-nature-pledges-can-help-fund-resilience

- Reuters. (2023, May 9). Ecuador seals record debt-for-nature swap with Galápagos bond. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/ecuador-seals-record-debt-for-nature-swap-with-galapagos-bond-2023-05-09/

- BNN Bloomberg. (n.d.). Interest in Credit Suisse-pioneered ESG debt swaps is soaring. Retrieved from https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/interest-in-credit-suisse-pioneered-esg-debt-swaps-is-soaring-1.2025049

- Grantham Research Institute. (n.d.). What are sustainability-linked bonds and how can they help developing countries? Retrieved from https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-are-sustainability-linked-bonds-and-how-can-they-help-developing-countries/#:~:text=Their%20aim%20is%20to%20improve,over%20budget%20priorities%20or%20expenditure

- Deacon, R. T., & Murphy, P. (n.d.). The structure of an environmental transaction: The debt-for-nature swap.

- BNN Bloomberg. (2024, December 3). BofA tenders bonds for Ecuador as new debt swap kicks off. Retrieved from https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/business/2024/12/03/bofa-tenders-bonds-for-ecuador-as-new-debt-swap-kicks-off/

- BNN Bloomberg. (2024, December 2). Barbados completes $125 million debt swap for climate resilience. Retrieved from https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/business/2024/12/02/barbados-completes-125-million-debt-swap-for-climate-resilience/

- BNN Bloomberg. (2024, December 17). UBS banker behind debt-for-nature swaps sets up credit fund. Retrieved from https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/business/2024/12/17/ubs-banker-behind-debt-for-nature-swaps-sets-up-credit-fund/?prefer_reader_view=1&prefer_safari=1

- BNN Bloomberg. (2024, December 11). Slump heralds slow demise of $319 billion market for ESG bonds. Retrieved from https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/business/international/2024/12/11/slump-heralds-slow-demise-of-319-billion-market-for-esg-bonds/

Important Information

The information herein is presented by RP Investment Advisors LP (“RPIA”) and is for informational purposes only. It does not provide financial, legal, accounting, tax, investment, or other advice and should not be acted or relied upon in that regard without seeking the appropriate professional advice. The information is drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but the accuracy or completeness of the information is not guaranteed, nor in providing it does RPIA assume any responsibility or liability whatsoever. The information provided may be subject to change and RPIA does not undertake any obligation to communicate revisions or updates to the information presented. Unless otherwise stated, the source for all information is RPIA.

The information presented does not form the basis of any offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of securities. Products and services of RPIA are only available in jurisdictions where they may be lawfully offered and to investors who qualify under applicable regulation. The RPIA managed investment strategies discussed herein may be available to qualified Canadian investors through private and/or publicly offered investment funds. Eligibility and suitability of investing in these funds must be determined by registered dealing representatives of RPIA or third-party dealers.

RPIA is a signatory of the UN Principles for Responsible Investment and as part of our commitment, we consider Environmental, Social & Governance (“ESG”) factors as part of our firm-level activities, including our investment process. ESG factors are important considerations in our investment management process but is supplemental to our primary financial and credit research and analysis functions. ESG factors that may be considered as part of our investment process include matters relating to climate change, energy use, energy efficiency, emissions, waste, pollution, matters related to human rights, impact on local communities, labour practices, employee working conditions, health and safety of the employees and affiliates, employee relations and diversity, executive compensation, bribery and corruption, board independence, board composition and diversity, alignment of interest between the shareholders and the executives, shareholder rights, and companies’ policies relating to ESG.

ESG integration, including components relating to issuer engagement, is a firm-wide investment approach but the weight and importance of it in our investment management process can vary across the investment funds we manage. Always refer to the relevant fund offering documents for important information on the investment objectives, strategies and associated risks of a particular fund. The consideration and implementation of ESG factors are also subject to RPIA’s internal investment and risk management policies and may be revised as a result of investment suitability requirements, current portfolio positioning and external market and economic factors.